Every real estate investor has their preferred ways to evaluate potential investments, comparing which asset may be best for their portfolio. Their goals are decision points, since some are looking for long-term gain while others emphasize near-term cash flow.

Some long-standing rules of thumb are not as useful as they once were, such as the 1 percent rule. This guideline suggests that the monthly rent on an investment property should equal at least one percent of the total cost of the property to return a positive cash flow.

But in a moment when prices are near record highs (outpacing even recent record growth in rents), it is difficult to find investments that meet those standards.

Two rules of thumb for evaluating rental property investments, which are based on different figures, are capitalization rate and internal rate of return, also called cap rate and IRR.

The knowable return vs. an uncertain future

The two ways of assessing an investment have upsides and downsides. Neither is necessarily better, and personal preference plays a role.

“They both matter,” says Doug Brien, co-founder and CEO of Mynd, who was among the pioneers in turning single-family rental real estate into an asset class, as he and his business partner explain in their recent book, The Big Long: How Going Big on an Outrageous Idea Transformed the Real Estate Industry.

“Cap rate really speaks to current return,” he says. “It’s more knowable.”

The danger of using IRR, he explains, lies in trying to get more data than is really available.

“It can be a fool’s errand to get wrapped around the axle on IRR,” he says, “which takes into account the time value of flows of money, including both current income and the ultimate sale of a property.”

At the time of purchase, few investors have an idea of when they want to sell.

“The ultimate value of a property and how far out in time the sale of the property happens has a huge impact on IRR,” he added.

For Brien, the problem with assessing future appreciation is that there is no single data source that is reliable.

“I’ve always believed in a conservative assumption of about 3-5 percent appreciation,” he says. “If you assume you’re going to sell in, say, five or seven years, you can calculate an IRR, but I don’t fixate on that, because to get it, I guessed about when I’m going to sell and what it’s going to sell for.”

Cap rate is more limited, but it can be more precise, he points out.

“With cap rate, I can be more accurate,” Brien says. “I know what the rent will be and I can make accurate assumptions on costs. What I know is what I paid, and I can pretty accurately forecast NOI [net operating income] because I can pretty accurately forecast rent and expenses.”

Brien is a confirmed cap rate guy.

“When I buy,” he says. “I’m focused on the things that are knowable.”

Cap rate: what do we know now?

Cap rate indicates the rate of return that a real estate investment property is expected to generate in a single year. The investor arrives at the cap rate by dividing net operating income by the property’s value; the figure is expressed as a percentage.

Cap rate assumes the property is bought with cash, using no leverage. It can be a great back-of-the-envelope way to compare investments.

The most popular formula is:

Capitalization rate = net operating income / current market value

In this equation, net operating income (NOI) is the expected annual income the property will generate (e.g., rent). NOI is calculated by deducting all the expenses for managing the property, including repairs and maintenance as well as property taxes, from the total income.

But, like any such rough estimation, cap rate’s utility is limited; it doesn’t take into account factors like leverage and what’s called the time value of money, or the varying value of a dollar at different times (because of factors like inflation).

Mynd also offers a cap rate calculator, where investors can plug in figures like purchase price, monthly rent, property taxes, and insurance to arrive at a cap rate.

The cap rate can also be used to arrive at a rough estimate of how long it will take to recover the amount invested in a property. For example, for a property with a cap rate of 5 percent, it will take 20 years, but for a property with a cap rate of 10 percent, it will take just 10 years.

To offer an obvious example, assume an investor wanted to compare two properties, one in a desirable city center, another in a more sparsely populated neighborhood. The former will pay a higher rent, but will also cost more to maintain, and the property taxes will be higher. For that reason, it will have a lower cap rate, because of its higher market value.

A lower cap rate goes hand-in-hand with a better valuation, higher likelihood of returns, and lower level of risk. By contrast, a higher cap rate suggests lower possibilities for return on investment, and thus higher risk.

IRR takes into account future projections

Except for houses that are bought to flip, most real estate purchases are meant to be held on to for more than the single year that cap rate looks at, so an equation that accounts for varying values of the investment over time are useful.

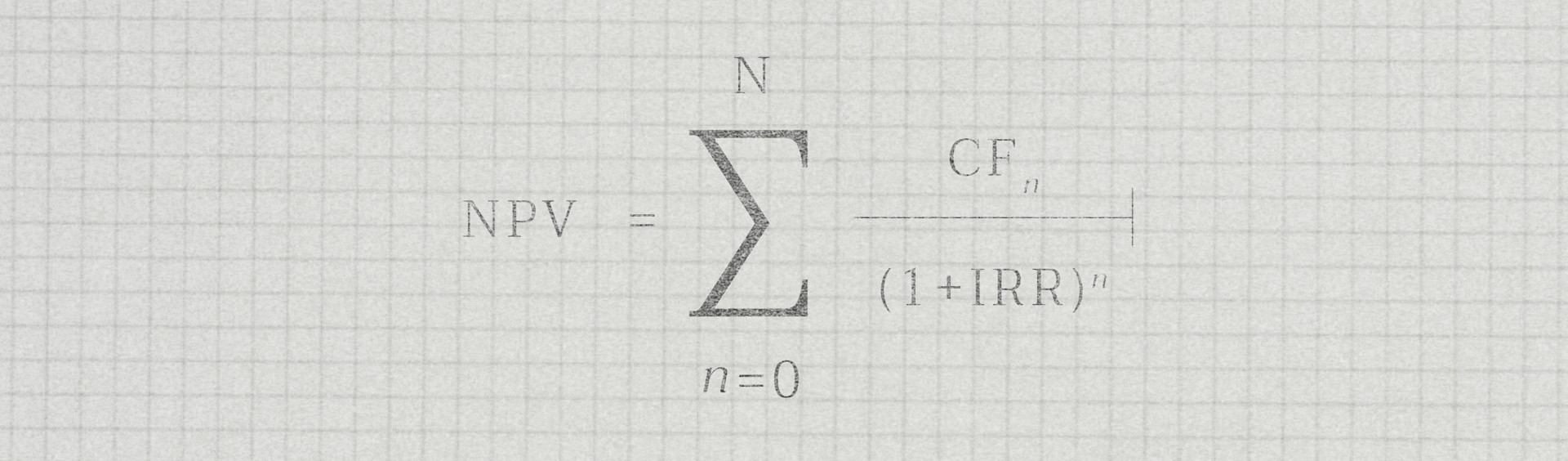

Internal rate of return takes more factors into account than cap rate, and the equation used to arrive at it is more complex:

To calculate the IRR, the investor would need to know the NPV, or net present value.

NPV = cash flow / (1 + i)t - initial investment

where:

i = required return or discount rate

t = number of time periods

For those who are not mathematically inclined, there are various calculators in programs like Excel that allow investors to plug in various values to arrive at IRR.

IRR lets investors know what they can expect to earn, on average, over an extended period of time, or lets them calculate what is commonly referred to as an annualized rate of return.

It brings together two main factors: profit and time.

Profit can be realized through income in the form of rent or mortgage payments, or in cash from the sale of a property, subtracting costs such as property taxes or repairs and maintenance.

Adding the variability of time to the equation adds a level of complexity. Trends in the housing market will affect the value of a property at any given point in time.

And various economic factors, including inflation, change the value of a dollar. As time goes by, the value of a dollar changes, and that changes the amount of profit on an investment.

The pitfalls of relying on cap rate alone

Dennis Bron, Mynd’s VP of growth, approaches the question slightly differently from Brien.

“People may say they’re buying on cap rate alone,” he says, “but really they’re making implicit assumptions about the return they’re going to get.”

Home values do have a tendency to increase over time.

“It may be that they think of appreciation as icing on the cake,” Bron says. “They’re not putting an actual number on the IRR. They’re thinking, ‘This is my cash flow return, and I try to buy in places that have upside on appreciation.’”

Buying strictly on cap rate alone might guide the investor away from growth markets.

“If you were not investing for total returns,” he says, “you might be more likely to invest in an $80,000 home in a place like Detroit, not cities like Charlotte or Raleigh. In those cities, you invest because you believe there is appreciation and rent growth.”

Thinking about the future naturally means making assumptions about the direction of the market.

“The advantage and disadvantage of IRR is that you have to make assumptions on various future numbers, and on all of those there’s a wide range and uncertainty,” he says, echoing Brien. “It forces you to think about those future developments that are critical to your return.”

The true test of IRR’s advantage comes at the time of sale, not purchase.

“IRR is, of course, really accurate when it is backward-looking, after you sell a property,” Bron says. “Then, it’s the best way to compare returns. When you’re looking forward, it’s much harder, but whether you’re putting a number on IRR or not, every investor is thinking about it.”